The Problem with Healthcare Data

This is not another blog post about the promise of real-world healthcare data. We all know that post already. It's also not a post on how much progress we've made over the past two decades, with the digitization of medical records and now, finally, interoperability.

This is a post about the problem that makes doing research and analysis with healthcare data extremely frustrating.

My co-founder Coco and I have been confronting this problem for the better part of the last fifteen years. And most days of the week, we talk to data analysts, researchers, and engineers from across the healthcare ecosystem - providers, payers, tech, and biopharma - who are all wrestling with the same problem.

When we say healthcare data, we're referring to structured and semi-structured claims, medical records, and other types of clinical data (e.g. labs, ADT, etc.). We're not referring to unstructured notes or radiology/pathology images. These types of data have their own challenges and we're not focused on them - at least not right now.

So what's the problem with healthcare data? Well it's not one, but actually three distinct problems:

- Normalization

- Data Quality

- High-level Concepts

Normalization

Normalization refers to a consistent and well-defined data model and data vocabulary. By data model we mean a specific set of data tables and columns. By vocabulary we mean the specific values individual records within a column are allowed to take.

It's very difficult to do data analysis on a dataset that is not normalized. And unfortunately healthcare data comes in all sorts of different data models and vocabularies.

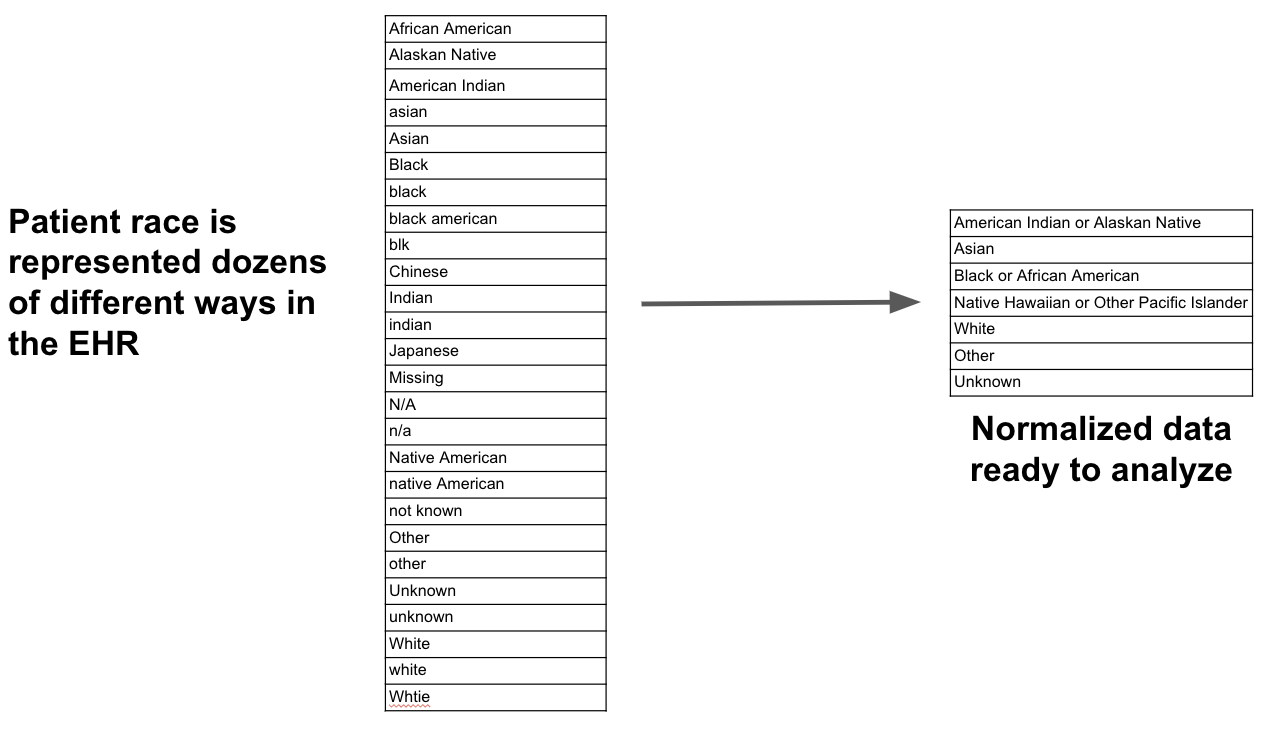

Let's take a simple example to make it clear what we mean by vocabulary. Consider patient race. If you inspect all the distinct values of patient race in your run-of-the-mill medical record system your likely to see something like the table on the left:

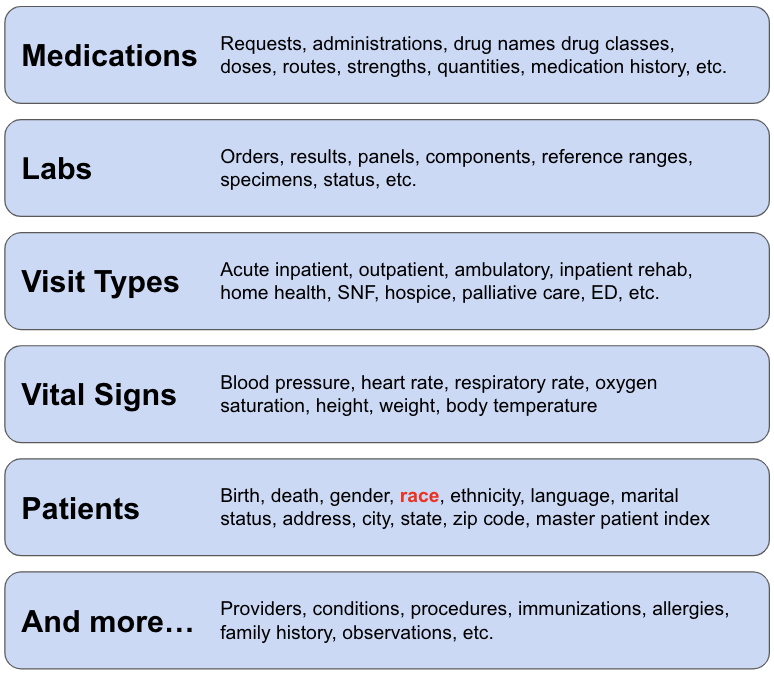

What we really want is the set of values on the right hand side. This normalized set of values makes analysis simple. However we rarely encounter data like this in healthcare, whether it's race or any number of other data elements:

In terms of data models the problem doesn't get any better. There are literally hundreds (possibly thousands) of healthcare data models. Every payer we've ever worked with has their own claims data model. Every medical record system has their own data model. Most providers and tech companies we talk to are designing their own data models.

There are also several so-called "common data models" such as OMOP, Sentinel, the Generalized Data Model, PCORnet, etc. These have gained traction to various degrees with OMOP leading the pack. The last count I heard was a few hundred organizations have mapped their data to OMOP.

Now at this point you might be thinking, "Excuse me, but wasn't FHIR supposed to solve the normalization problem?" I think I did hear that, but in my experience it hasn't. I'm not knocking FHIR - it's been great for interoperability. But it hasn't solved the normalization problem. There are many customizations (i.e. profiles) to choose from and different organizations implement FHIR differently. And perhaps just as important, FHIR doesn't work for analytics (but that's another post).

Data Quality

There are three categories of healthcare data quality issues: missingness, duplication, and implausibility.

Missingness is very common in healthcare data and is perhaps the single biggest data quality problem:

- Medical records are often missing visits a patient has at practices outside their system that are on a different medical record system

- Claims data by definition does not include clinical data such as lab test results

- Care teams can forget to document problems, signs, symptoms, medication histories, etc., leading to missing diagnoses in claims and medical records

- We rarely know if patients actually take prescription medications - we can only infer from presciption fills / refills

Duplication is also common and can manifest in many different ways:

- A single patient can have multiple birth dates or death dates

- A single claim can be represented multiple times thanks to adjustments or denials

This problem gets even more complex when you're working with multiple datasets simultaneously. You end up with multiple IDs for the same patient or the same encounter, resulting in the need to de-duplicate patients and encounters before you can do any analysis.

Implausibility basically means there are two pieces of information in the dataset that don't agree:

- A patient is male but has diagnoses or procedures that only apply to females

- A patient is a child but receives treatment only relevant for adults

Many data quality issues are relatively simple, like several of the above examples. But many data quality issues are hidden because they depend on defining high-level concepts to find them.

For example, the fact that a patient hasn't had any dialysis visits in the last couple of months isn't particularly interesting or indicative of a data quality problem, unless you happen know the patient has end-stage renal disease. If you know this additional piece of information, then you're possibly missing dialysis visits, a kidney transplant, or mortality information (because without dialysis or transplant the patient is likely dead). But you can't begin to assess this potential data quality problem unless you have already created a high-level concept to define patients with end-stage renal disease.

High-level Concepts

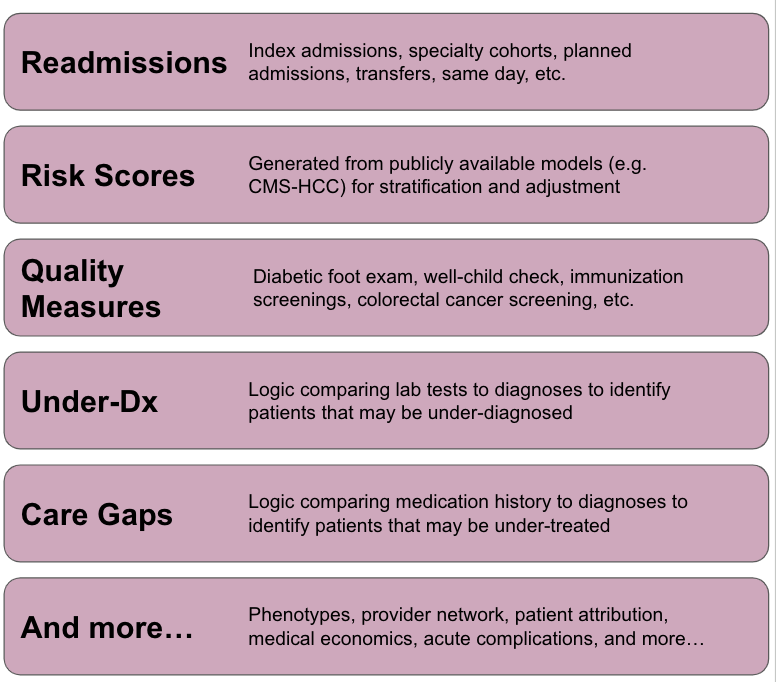

Defining high-level concepts isn't just necessary for identifying data quality problems, it's almost always a pre-requisite for any interesting analysis. Think of a high-level concept as a new column in the data model that is created from the raw, atomic-level healthcare data. Here are some examples:

- Does a patient have a certain condition (e.g. type 2 diabetes, chronic kidney disease, multiple myeloma)?

- Is a patient taking a drug (or class of drug) indicated for a condition they have been diagnosed with?

- Was a particular claim for services rendered in an acute inpatient care setting?

- Does a hospital visit qualify as an index admission or readmission?

Unfortunately this short list of examples isn't even the tip of the iceberg. There are literally thousands of high-level concepts that need to be created for common research and analysis use cases:

The challenge in creating high-level concepts is they require a ton of subject matter expertise, about healthcare data, healthcare delivery, and medicine. Often times you need clinical knowledge to create high-level concepts. But the people who tend to be best at this work tend to have a mix of these skills. These are the folks that can rapidly build useful concepts and translate clinical input (when they need it) into analytics-ready data.

Conclusion

So why does this problem exist and what can we practically do about it?

Like most things, I believe it ultimately boils down to incentives. If the incentive were to have the highest quality healthcare system, then we'd already have the "learning healthcare system" we all talk about and analytics-ready data would be at its core.

Instead, a lot of our energy is spent trying to get paid or deny payment for healthcare services, and our data collection systems (e.g. EHRs) have been optimized to do just that.

Of course the problem is multi-faceted, but I believe that's the crux of it.

To fix it, people like to say "let's re-engineer the EHR from scratch." But this won't matter (or happen) unless incentives change. And even if it does, data quality and high-level concepts won't be completely addressed by this.

Unfortunately I don't think there's an easy answer, which is why the problem has gone unaddressed for so long. For better or worse, Coco and I started Tuva to solve this problem, which we're 100% dedicated to (Tuva or Bust).

In future posts, I'll dive into each of these problems in more detail and talk about how we're solving them at Tuva. In the meantime, check out the thetuvaproject.com to explore the open source or contact us at Tuva to learn how we can transform your organization's healthcare data to unlock advanced research and analysis.